The Paris Manuscript

Last month I had the fortunate opportunity to take several hundred pictures of a manuscript that is preserved at the Musée Guimet in Paris. It is a handwritten text of one of the first commenatries of the Same Intention (dGongs gcig), namely the sNang mdzad ye shes sgron me composed in the 1250s by one of Sherab Jungne’s direct disciples, Dorje Sherab. The manuscript has several exciting features, some of which I would like to briefly communicate here.

1. On the reverse of the first page we find two miniatures. The left one is most probably a portrait of Kyobpa Jigten Sumgön, showing the teaching mudra (you can click on all photos to enlarge them):

This is a very close copy of the Thanka decribed by Amy Heller in her article “A Thang-ka Portrait of ‘Bri gung rin chen dpal, ‘Jig rten gsum mgon (1143-1217)” published in JIABS no. 1 (October 2005): 1-10. The thanka was carbon dated to the early 13th century, and Amy concludes that it is likely “a commemorative portrait which was made shortly after the death of ‘Bri gung Chos rje Rin chen dpal in 1217.”

On the right hand side of the reverse of the first folio we find another portrait of a Lama holding his hands folded in prayer, facing Jigten Sumgön. A probable suggestion is that it shows Jigten Sumgön’s disciple Sherab Jungne (1187-1255), who wrote down the vajra-sentences of the Single Intention of his teacher and taught them extensively after 1225. He was also the direct teacher of the author of the sNang mdzad ye shes sgron me.

The style of these miniature paintings is copying that of the thanka, which was dated to the early 13th century.

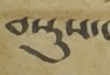

2. Several features of the handwriting suggest also an early date for our manuscript. One of them is the use of ancient orthography. Some examples:

Other ancient features are the way in which some of the letters are stacked, which resembles the writing style we find as early as in the Tibetan documents of Dunhuang:

These and other features of the manuscript could mean that it was written as early as the 14th century (according to a preliminary assessment by Sam van Schaik). Unfortunately, however, the knowledge of styles of Tibetan handwriting from the 11th century onwards is not much developed and thus the dating must remain open for further investigation.

3. Another interesting fact about this manuscript is that it was brought to Europe by the French explorer and dedicated Tibetophile Alexandra David-Néel. She is known to have spend several decades of the first part of the 20th century in and around Tibet. In 1911 she travelled to Sikkim where she became friends with Sidkeong Tulku Namgyal, the Maharaja and Chögyal of Sikkim. During her stay she met the 13th Dalai Lama twice and also traveled into Tibet to Shigatse to meet the Panchen Lama in August 1916. Later, in 1924 and after a fantastic journey through China, she reached Lhasa disguised as a beggar and stayed there for about two months. Again in 1937 she travelled in the Eastern Tibetan highlands and spend time in Tachienlu (Tib. Dar-rtse-mdo). It would indeed be very interesting to find out on which occasion she got hold of this manuscript. The answer might be buried somewhere in her extensive letters archived in Digne Les Bains in the south of France.

4. The photographic documentation of this rare manuscript is a crucial first step for editing the commentary. What makes this manuscript particularly valuable are its countless annotations between the lines. These contain specifications of quotations and alternative readings, some of which might go back to another transmission of the text. (click on the photo to enlarge it)

What a beautiful manuscript, thanks for putting it up for us!

I notice at the end of the 7th line of black letters are two examples of syllables written in the kind of shorthand that utilizes numbers to replace part or all of the syllable. And there, too, is an example of using what looks like the reversed letter ‘na’ to stand for the negative med (‘is not’ or ‘does not have’).

I know of a manuscript made in the 1240’s copying a manuscript made in earlier in that century that incorporates still earlier manuscripts, and it makes use of just those ‘Old Tibetan’ features you see in your manuscripts (but not in cursive script as yours is). So it seems sure that conservative scribes could continue scribing these O.T. conventions way into the Mongol period.

Yes, the fact that it is cursive script is interesting. I have only mentioned a few of the features that I found on the first few pages. They are found throughout the ms. In my first reading of the colophon I couldn’t discover any additional remarks. I guess apart from carbon dating it, it will be difficult to know whether it is an early ms or a faithful copy of an early one.

BTW the editors of the 2009 Varanasi edition of the text have included some of the interlinear notes in their footnotes as “Ham par”. I guess that means “Hamburg print(!)”, because they took the notes from what was legible in a photocopy of the ms existing at Hamburg University. I plan to publish the photographs as soon as I have a bit of time for some photoshop sessions.

So I suppose it you were to photocopy the Paris manuscript you could call it the “Par-par”? That sounds a lot like a butterfly, or a pasta shaped like one. Still, if you’re ready to photoshop, don’t let me hamper you, so to speak. BTW, How are you coping up in Hagen?