Tibetan Mo: An Interview on Divination with Khenchen Nyima Gyaltsen

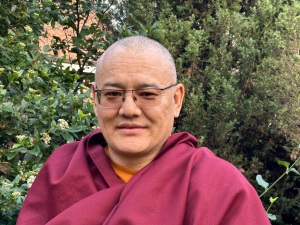

Khenchen Nyima was born in 1976 in Tibet and entered at the age of eleven at Lho Lungkar (Kham) the monastery Ogmin Thubten Shedrub Ling, where he underwent traditional studies for six years. In 1994, he left Tibet and studied for ten years at different Tibetan Buddhist institutions in India. At the beginning of 2002, he was authorized to teach at the Kagyu College at Jangchub Ling (Dehradun, India) and in 2004 he was enthroned as a Khenpo (teaching professor) of that College. In 2013, he became the Head Khenpo of all Drikung monasteries in exile.

The interview with Khenchen Nyima took place at the beginning of August 2016, at the Milarepa Retreat Centre, Schneverdingen (Germany), where he led a study program for translators. As an opener, we first discussed a brief passage from the colophon of a Tibetan text. In this autobiographical passage, the Tibetan historian and Tantric master Amé zhab reports the following incident:

When I had reached my nineteenth year, on the third day of the second month of the hare year (1615), (…) I saw again and again in my dream clearly [Mahākāla] Gurgi Gonpo with eight deities in the midst of rainbows, clouds and masses of flames on top of the Eastern Mountain of Sakya. [Upon reporting this to his teacher Müchen Sangyé Rinchen, the guru said]: “This is not a positive sign since it is a confused appearance of the mind, and the mind is beyond expression since it is unborn. It is also not a negative sign. If we decide that it is a pure vision purifying a few veils of the mind, it is [all right to leave it] like that.”

Question: What is the difference between Amé zhab’s dream sign and a sign occurring through a divination ritual? If we compare the two, could the sign appearing through the Achi Mo not also be a confused appearance of the mind?

Khenchen Nyima: Yes, because here [pointing to the Tibetan text passage translated above] it says regarding Amé zhab’s dream that he saw the appearance of Lord Mahākāla. He asked his guru about it, and the teacher said that it was not particularly good or bad. So, when we think of someone who is an authentic religious practitioner, it is said that there is no talk about good or bad. However, in mundane terms, if gurus, tutelary deities, protectors, and so forth, appear in someone’s dream, then it is considered a good sign. That is the way of the world. Now, concerning these words of the guru who said that it is neither good nor bad—if we think in terms of someone who is an authentic religious practitioner, then it is said that he should not make any particular divisions of good and bad. [Therefore, this dream vision] is not a particularly good sign. Since [the dream] is a mental illusion, all sorts of things might appear—sometimes it might occur to us to be good, sometimes it might occur to be bad. On the other hand, however, it is [in a religious sense] also not [only] bad.When one is practicing religion, gradually the veils [of illusion] will be purified bit by bit, and different pure appearances will occur. [The main thing is] that [as a religious practitioner] one should not keep hopes and fears about [such things] being specifically good or bad.

In general, Jetsün Milarepa said a lot of similar things to Dagpo Rinpoche (Gampopa). Sometimes when Dagpo Rinpoche meditated, appearances of the buddhas occurred [to his mind]. “Now I am probably quite good because I see the buddhas,” he said to Jetsün Mila. However, Mila replied: “Oh, that is nothing particularly good or bad! Because of the different movements of the wind energy (Tib. rlung) in your [inner] channels (Tib. rtsa), you see such different appearances. Do not keep any hopes or fears about those!” So when the great Müchen talked in that way to Amé zhab, he was probably talking within a similar context. When we speak of someone who is an authentic religious practitioner, he should not have hopes and fears, and so there is no good or bad [in that sense]. This is what he seems to be saying.

Someone who has a very firm faith in Achi, a lama, performs the divination with the purpose of benefiting the people. [When he does that], he temporarily accomplishes the objectives of other sentient beings. [Ultimately], he works to accomplish the activities of awakening for the sake of others. When one performs the divination, one supplicates Achi. One thinks she can cause anything to happen through her activities of awakening. [That means] to make divination with faith. In the divination, sometimes good and sometimes bad [signs] occur. They occur from supplicating Achi. It is like when we do an exam: the results come from [our efforts]. That is the difference between the dream appearances in the case of Amé zhab and the good and bad [signs] in the case of divination [which occur through supplication].

Question: In the case of the signs that appear to the lama who performs the divination, if they are not the confused appearances of his mind, how are they the activities of the awakening of Achi?

Khenchen Nyima: When we talk about performing divinations, an accomplished yogi does not need any divination, right? [He does not need to know]: “Does it look like I will get sick? Will I die? How might this turn out for me?” An authentic religious practitioner does not need such divinations. Jetsün Milarepa, for instance, did not ask other people for divination. [He did not ask]: “Will it be good if I go to Lapchi [mountain]? Will it be good if I go to Mount Kailash?” Also, he did not perform divinations himself.

For which purpose does one do divination? If, for instance, an ordinary person plans some undertaking or loses a valuable thing, or he or his parents or relatives are sick—which method can be applied to help in such a situation? He is perplexed. He does not know where to search [for the lost item], or whether it would be appropriate to change the doctor or the medicine. He has carried out many undertakings in the past that may not have been completed, and he still has more plans for the future, but does not know what their prospects are—what does such a mundane person need? He needs to ask the lama, right? He needs someone to perform a divination.

Regarding the person who performs the divination, if it is someone clairvoyant, he can probably say it directly [and does not even need to perform divination]. If that person is not clairvoyant, he needs to supplicate a deity, like Achi or Palden Lhamo. He directs the question to the deity and asks: “How will it turn out? What is the best method for him?” The requestor of the divination asks the lama, and the lama performs the divination accordingly. When [the lama] receives the prognosis, he proceeds accordingly. He says: “According to the prognosis, that sick person will probably get cured.” Or: “He probably needs to go to another doctor.” If something has got lost, he might say: “If you search it in the eastern direction, you will probably find it,” all in accordance with the prognosis.

Anyone who performs the divination first has to do the practice [of the sādhana]. For instance, even [an experienced] lama performing the Achi Mo first has to recite a lot of Achi mantras and accomplish Achi completely. Therefore it is said here [in the sādhana] that one has to practice until the signs occur. That means, for instance, that through the practice of this Achi sādhana you receive dreams where you see her face. It is not as in the case mentioned before, where a good dream [is seen as neither good or bad] in the practice of a Mahāmudrā yogi. Here, when one achieves a sign through the practice of Achi, you see the sign as a valid proof of [success in] the practice of Achi. When one is convinced that it is like that, one proceeds by performing the divination.

If we analyze properly, this kind of sign is an appearance of the yogi’s mind. In general, there are many types of appearances of the mind: Confused appearances, karmic appearances, conditioned appearances, the pure appearances of yogis—there are many levels. According to this analysis, the appearance of signs [in the practice of Achi] can be [understood as] appearances of a yogi who has purified his karma. As the great Müchen said above: [The appearance of Mahākāla in a dream] is also not bad because it is a pure appearance arising due to a slight purification of mental veils. Müchen did define it like that, right?

Thus, when someone wants to perform the divination, he [first] practices the Achi [sādhana], and when signs occur in his dream, he must form the clear determination: “Having practiced Achi, this is a sign and valid proof of that practice.” Moreover, when such appearances get progressively more sublime, we can apply an explanation in terms of the view of Mahāmudrā, namely [that such signs are] still slightly confused appearances. There are many levels of confused appearances. If we take water as an example, when hell-beings look at water it appears [to them] as something like burning lava, hungry ghost perceive it as mucus, human beings see it as water, but yogis [with pure perception] see it as the nature of the goddesses. When the minds of the beings get progressively purified, the appearances change in accordance to [the level of] the purification. Similarly, when someone practices Achi, and the sign and valid proof of the practice occurs, generally, those are appearances that are still slightly confused, but these are not like our usual confused appearances. When one performs divination while having confidence concerning these [purified, but still slightly confused] appearances, one can temporarily accomplish the purposes of oneself and others. On the basis of that, it is possible to help. [The divination] can temporarily clear away the problems for those who make an inquiry. Based on that [the lama who makes the divination] can also benefit other persons by bringing them onto the path of religion.

Question: Is that what is called “the awakened activity of Achi?”

Khenchen Nyima: Yes, that is what is called Achi’s awakened activities. When we speak of “activities of awakening,” these consist not only in bringing all sentient beings to Buddhahood. Generally, Buddha activity is to bring sentient beings to Buddhahood. Persons with Śrāvaka potential are brought to the level of the Śrāvakas, those with Pratyekabuddha potential to the level of the Pratyekabuddhas, and those of the lower realms to the higher realms. The suffering of those who have great suffering is pacified, and the illnesses of the ill is cured. In brief, the activities of awakening accomplish temporary and ultimate benefit and happiness for sentient beings. All these activities [with temporary and ultimate results] are called Buddha activities. Accordingly, the performance of the Achi divination can accomplish many temporary purposes of others [and thereby lead them to the ultimate path].

If you are a beginner on the path, you might wonder: “Which place would be good for a retreat? Would it be appropriate to go for a retreat to the Lapchi Mountain? Alternatively, is it better to stay here for a retreat in Germany?” A person without a high realization needs to know for a retreat whether particular problems may occur at that place, for example regarding food. In that case, one can turn to the Achi Mo, which has [for each prognosis] a section called “outlook concerning the religious activities.” This section provides a prognosis about how religious activities will turn out. The prognosis may be that it will turn out very well, or that there will be problems, like getting sick. In that way, the diviner can perform the Achi Mo for the sake of beginners concerning religious activities.

Most other sections concern worldly issues: Will a sickness be cured? Will travelers return? Will I have a son? Will I get pregnant? Will my business go well? Such divinations are necessary since worldly people have those kinds of problems. Religion is also meant to clear away the problems of worldly people, right? Moreover, the text offers many practical methods to clear away problems. Sometimes it is recommended to request certain religious activities [to be performed], sometimes problems need to be cleared away by [ritual practices such as] beating drums and making tormas, and sometimes there is the advice to consult a different doctor regarding an illness. In that way, the problems of others are cleared away. These are Achi’s awakened activities that are in accordance with religion.

Question: How does the divination relate to the “supramundane” level?

Khenchen Nyima: It is not appropriate to ask for divinations directly concerning supramundane matters, like asking whether one will reach the first bodhisattva bhūmi [in this lifetime] or not, or whether one will achieve Buddhahood, and so forth. However, according to Jigten Sumgön, there is an indirect relation to the supramundane path. He says in the Single Intention (2.11) “the sixteen pure codes of human beings, and so forth, and the divine codes have the same vital point.” When he says, “pure codes of human beings,” that refers to the conduct in the society of human beings; it is about being a good person, and so forth. Other scholars hold that the “pure codes of human beings” are a mundane religious practice, which is different from the “divine codes” because one has to give up saṃsāra to practice them. Jigten Sumgön, however, maintains that it is not like that. He teaches that the human codes and the divine codes have the same vital point.4 Based on the practical methods of this divination manual, the pure codes of human beings will become authentic, and that will benefit the divine [supramundane] religious activities. Temporarily, in the mundane world, we need things like long life, freedom from illnesses, and material enjoyments. The divination helps to create conditions conducive to those needs. In this way, the divination manual is a means to make the supramundane path arise authentically in the mind-streams [of people].

Question: How can the Mo-practice be described in terms of “conventional” and “ultimate” truth?

Khenchen Nyima: When we speak in terms of the conventional and the ultimate, the performance of divination is a conventional practice. Generally, in the ultimate truth, there is no performer and no receiver of the divination. In the ultimate truth, there are no things like a mālā [or dice, and so forth] to perform the divination. In the context of the conventional truth of ordinary beings, however, we have categories like “performer” and “receiver” of the divination. These exist as separate categories, and based on the appearance of these persons and things we perform the activity of divination. Therefore, generally, divination is conventional reality, it has a provisional meaning. When we speak of provisional meaning, it means that the divination helps to prevent problems and troubles and guides one unto a convenient path. Thus, the prognoses offered by the divination provide guidance that helps to avoid unfavorable conditions and paths and achieve favorable conditions and paths.

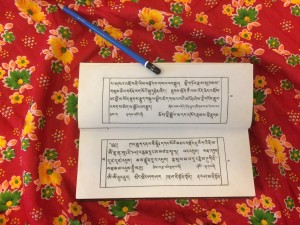

The Achi Mo [is done with dice] showing three to eighteen dots, [i.e., sixteen possible results]. [Each of the sixteen sections starts with] an explanation about how your religious [activity] might turn out. It is an explanation about how it might turn out when you are really practicing the essence of the Buddha’s doctrine, the Dharma. You find this explanation at the beginning of each of the sixteen sections. It is regarded as the most important [part of] the divination. Below that, there follow [the explanations for] the mundane issues.

Actually, Achi’s main awakened activity is concerning the supramundane [path]. Therefore [in many sādhana’s of Achi] it says:

You combine the power over the three spheres of existence, you protect all beings,

and you guard the teachings of a thousand buddhas.

You accomplish the wishes of beings in accordance with the Dharma—

I pay homage to the wish-fulfilling Achi!

When it says, “protecting all beings,” that includes the Achi Mo. It refers to helping the beings. When one determines a person’s positive or negative prognosis based on the Achi divination, one accomplishes her awakened activity concerning the mundane level. However, if one asks what Achi’s main awakened activity is, then it is bringing all sentient beings to Buddhahood. It is guiding the beings [and fulfilling] their wishes in accordance with the Dharma.

Yet, to guide the beings to the path of Dharma, first one has to proceed based on the practical methods of the mundane path. Therefore, the Indian master Ācārya Bhāvaviveka says:

Wanting to climb to the top

of the great mansion of absolute truth

without the ladder of pure relative truth

is not suitable for a learned one.

Based on the authentic, mundane, conventional practices, one climbs to the top of the great mansion of the ultimate. The conventional is like a ladder. Therefore, the divination is like that ladder that is the conventional reality, a Dharma of provisional meaning. However, based on that, it leads into the path through which Achi can bring all sentient beings to Buddhahood. Therefore, Achi’s main awakened activity concerns the supramundane path; but to accomplish that path, one must first practice the mundane practical methods. That is the reason why the Achi divination has appeared.

Question: Is it possible to ask other questions than those that are making up the various categories of prognosis in the divination manual? Could one inquire through the Mo whether it would be appropriate to start a meditation retreat now or later, and which practice one should emphasize?

Khenchen Nyima: The manual has no specific category for retreats. However, you can include it in the main category that is concerned with the category “outlook concerning the religious activities.” The lama can make two divinations: one concerning the present year, one concerning the next. If the divination concerning this year turns out better, then it is appropriate to start your retreat in this year. In such cases, we have to include the many small activities [in the main categories] like that.

Question: So it is appropriate to ask such questions concerning meditation retreats, and so on?

Khenchen Nyima: Yes, it is appropriate! Usually, as I said before, the advanced yogis do not have to determine [such a question] in that way. They determine it by themselves. Jetsün Mila said that one should not cheat oneself with divinations, astrology and so forth. It is [more] appropriate for an advanced yogi to determine [such questions] by himself. However, if one is a beginner like we are and is unable to determine [things] like that, one proceeds by way of divination. Mainly it is about faith, right? If divination about going to retreat this year turns out well, then, thinking “this year I will not get obstacles,” one proceeds with this thought in one’s mind. In that case, if you go this year, you will not get sick, you will not face problems, and the retreat will be good. However, if the lama says that the divination for this year is not good and one nevertheless enters into a retreat, then one lacks faith in one’s mind. If one thinks that one has to enter the retreat despite the bad prognosis, then one lacks the comfortable feeling in one’s mind. [As a consequence], one probably will face problems. There is a great relation [between occurrences and] the feelings of one’s mind.

Question: There are many types of divination. Some people use dice, some a mālā, others a mirror—what are the main differences between those? Is there a method that is particularly suited for accomplishing the supramundane religious activities?

Khenchen Nyima: As I see it, there are probably no particular differences. Some people use a mālā, some use dice, and then for some people there seems to be the so-called unique accomplishment of mirror-divination of Achi. In the mirror-divination, one looks into a mirror and whatever is going to happen will appear in the mirror. For this [practice] one has to be a particular type of person possessing the so-called mirror-divination-eye. In most cases, people use either dice or a mālā. However, people who have transformed the channels in the body may have the mirror-divination-eye. If we take something like a bird of prey, it has the eye-capacity to see the prey many kilometers away. Likewise, some persons have special abilities in the channels of their eyes. Thereby, having accomplished the mirror-divination like that, some people can determine [issues] by looking into a mirror. Otherwise, however, most people perform divinations using either a mālā or dice, whatever is convenient.

Question: There is no difference?

Khenchen Nyima: There does not seem to be a particular difference between those two. It does not seem to be the case, for instance, that if one uses a mālā, it is for the sake of religious activities and if one uses dice it is for the sake of mundane issues. However, when one is using dice, there is a difference regarding the way the dice-holes are made in dice for playing games and in dice for divination. I do not remember this well or clearly, but if the number one is on this side, some dice have the number six here [on the opposite side]. The dice for divination and the dice for playing seem to be a bit different. However, I do not remember the details.

Question: Is there a difference between Buddhist divination and Bönpo divination?

Khenchen Nyima: There is probably a slight difference, right? Mostly they are quite similar in scope. The divinations that our Buddhist lamas perform and those that the Bön lamas perform … it is hard to say. Long ago, in the very beginning, the Bönpos probably used divination first. In my view it is like this: When the Buddhist lamas saw that the Bönpo lamas used divination, [they decided that] we Buddhists also need divination. By attaching our own deities and protectors to the practice, a Tibetan Buddhist tradition of performing divinations came about. There was probably also a mutual exchange [of the elements of divination]. The most important aspects [of the divination manuals] in both [traditions] are probably very similar. However, in the performance of their [respective] divinations, there are differences concerning the deity practice.

Question: Regarding the lama who performs the divination—what are his specific characteristics? Is it also appropriate when other practitioners perform divinations?

Khenchen Nyima: Concerning the person who performs the divination, we usually say that it is done by a “high lama.” That does not mean that he has a high throne or that someone with a low throne must be a low lama. A “high lama” is one who has the qualities of abandoning [the veils] and accomplishing [the qualities]. The more qualities such a person have accomplished, the better the divination will turn out when he performs it. [As the text says], one has to accomplish [the deity]. Possessing the qualities of abandoning [veils] and accomplishing [qualities], one has accomplished the deity.

Someone who performs the Achi Mo has in the best case the qualities of abandoning and accomplishing. He can directly see Achi’s face; he can directly converse with her—if it is such a lama, he can perform the divination most perfectly. However, it is not always possible like that. Generally, in deity practice, we talk about three ways of accomplishing the deity. The first is the accomplishment of signs, the second the accomplishment of the number, and the third the accomplishment of time. In deity practice, the accomplishment of signs means that one can bring forth all the signs of accomplishing the deity. That is called the “approach of the sign” [i.e., mantra recitation until the signs appear]. The accomplishment of the number means that even if one cannot bring forth all the signs, one accumulates the mantra recitation exactly as it is prescribed, such as 100.000 recitations. That is called the “approach of the number” [i.e., mantra recitation until one accomplishes the prescribed number of recitations]. Accomplishment of the time means that one has accumulated mantra recitations for the required time. Here, for performing the Achi Mo, the minimum requirement is that you have to accomplish the required number of mantras, i.e., you have to do the mantra of the sādhana 100.000 times. That kind of characteristic definitely seems to be necessary.

Question: Thus, if he has accomplished that minimum requirement, an ordinary religious practitioner too can perform the divination.

Khenchen Nyima: There are also a lot of people [like that] who practice and perform divinations. Other people, however, out of principle never perform divinations. For instance, if you were to request someone like Jetsün Mila to perform a divination, he would probably scold you. In our Drikung Kagyü tradition, if we requested Drubwang Rinpoche to perform a divination, he would scold us. He said: “We are monks! We are religious practitioners! Just practice religion, and then all issues will be solved! Why should one perform divinations? This so-called divination is for the sake of the mundane laymen and women!” He would never help us with divinations. Other lamas will perform divination out of kindness when a monk or layperson asks him to perform one. It is up to the individual lama, right?

[Khenchen also explains later that the person performing the divination should not just take the outcome literally, but should count on his intuition about the outcome. The best would be to combine the divination with astrology as Lamchen Gyalpo Rinpoche did.]

Question: Are there also monks, yogis, and other lamas requesting a lama to perform divination?

Khenchen Nyima: Yes, the requester could be anyone. It is possible that sometimes one lama might request another one to perform a divination, as one doctor goes to another doctor [when he is sick]. He cannot do an operation on himself! [He laughs]. Likewise, it is possible that a lama, a monk, a layman, a laywoman, an old person, or a young person might ask a lama to make a Mo.

Question: But most people who make an inquiry are lay people?

Khenchen Nyima: Mostly this divination is for the sake of the lay men and women. As I said before, it is mainly a practical method for helping with the problems and troubles of mundane people. There are great problems and troubles for the ordinary people, right? Therefore, one needs to perform divinations for their sake.

Question: Does the lama who performs divination thereby generate income for his monastery?

Khenchen Nyima: There is no specific fee for performing divination. If you give an offering, that is fine, if you do not give an offering, that is also fine. You mainly have to offer your faith. You need to have faith in the one who is performing the divination. You have to offer your faith, and if you offer a gift on top of that, it is fine, if not, it is also fine. The performance of divination is not for the sake of business. If it were, there would have to be an exchange of object and payment, but divination is not like that. Mainly, one needs to have faith in the lama and the divination. Without that, the divination will not benefit you.

It will be just trouble for you. In the monastery, we usually do have divinations, pūjas, group prayers, and so on. However, that is not for the sake of generating income for the monastery. It is mainly for the sake of helping the people. On the other hand, it is a tradition that the people individually make offerings that the monk community is allowed to use. Divinations and pūjas are not specifically for the sake of improving the monastery’s economy; they are mainly for the sake of helping the mundane people. We have a saying: “If you throw a stick upwards and fruits fall down, there is profit.” [He laughs]. If I stand underneath an apple tree and just by chance throw a stick upwards, and if some apples fall down because of that, then I have to eat them. If I throw them away, it is a waste. Likewise, it is often so that divinations are done, and when the divination is done, an offering is made to the lama, and the lama uses the offering for the monastery. That is the general situation, but we do not perform a divination to get money. It is possible that some strange person performs divination for the sake of money.

That is different. The religion taught by the Buddha, the Exalted One, is a method for clearing away the problems of sentient beings. That is what he has taught. However, it happens that some person uses religion as a business for making a living. That is not the problem with the religion; it is a problem with that person. Likewise, it is possible that someone performs divination, thinking “based on performing the divination I will make good money.” I cannot say that there is nobody like that, right? However, from the religious perspective, divination is not for the sake of that.

[The Interview was translated by Solvej Nielsen. The Interview together with an introduction and a translation of the Achi Mo was published in Jan-Ulrich Sobisch, 2019 as “Divining with Achi and Tara: Comparative Remarks on Tibetan Dice and Mālā Divination: Tools, Poetry, Structures, and Ritual Dimensions, Prognostication” in History 1, Leiden: Brill. If you would like to have a copy of my translation of the Achi Mo, drop me a note at jusobisch@gmx.de].

Thank you Jan, I hope you are well and all your family. Happy spring, best greetings , Amy

>